I have been doing a lot of reading about fencing design. I checked out about a dozen books on fencing from the library, but found them all to be inadequate in their treatment of non-decorative, practical fencing for livestock. So, the “Interweb” (as Kirk likes to call it) helped me a lot. These nice folks at Gateway Farm Alpacas have the best advice, by far, that I have found for installing field fencing, which is the type I chose to use. I also found good help on the websites of fencing manufacturers, with installation instructions for their own products.

It occurs to me that perhaps the most important component of any fence under tension is the end-bracing. Granted, I’m not doing a high-tensile fence, but field fencing still takes plenty of stretching to make it strong and non-saggy. I have come to realize that there isn’t a lot of good advice out there about designing end-braces, or the “why” behind the design. And as I drive through our county, I see many more examples of failed end-braces than successful ones. So, after a lot of reading, studying other people’s mistakes, and thinking, here is what I’ve concluded on the end-brace debate. Now, I’m no mechanical or civil engineer, I’m of the electrical bent; but I did have to take a few ME and CE courses in college, enough that I grasp the basics of statics & dynamics, and physics. So, here is my stab at explaining what happens to end-braces, why they are prone to failure, and how to best ensure their strength and longevity.

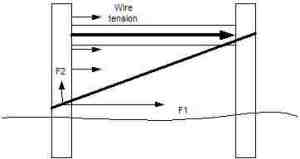

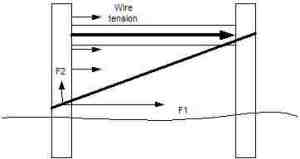

The first step is to think about what is happening to the end post on which multiple horizontal wires are pulling. The most concerning point is near the top of the post, due to torque (think of a long lever…), the force on the post is greatest here. The post, especially if you didn’t bury it really deep, is going to want to “flip” sideways out of its hole. This is because the bottom isn’t going to experience enough resistance from the soil to counteract all that force on the top of the “lever.” The soil is going to “give in” and erupt vertically, allowing the post to migrate and eventually lean, which allows the fencing to become slack at the top. This will mostly likely happen very slowly over years; though I have heard of it happening to people the instant they tensioned the fence, if they did an especially poor job of brace design! Here is a picture of what this lever action looks like:

Additionally, the post is also going to want to bend, because its tensile strength is being challenged. This part is easier to address by using very thick (usually 6″x6″) posts with no flaws, which offer greater tensile strength. So, that just leaves the leaning tendency to fix. There are many solutions people offer to address this problem. But I feel the most practical and wisest solution is the “H-brace.” The idea is to transfer most of this load to a second post, and allow that post transfer the load back to the bottom of the first post, offering a counter-force. So, first let’s focus on transferring the load to the second post:

By putting a horizontal beam in between the end post and second post, it’s easy to see that much of the load on the first post will now be pushing on the top of the second post. But, this, by itself, is no help; because of course the second post is now going to want to “flip” in a clockwise direction too. What’s needed is a diagonal wire wrapped around both posts, tied back down to the bottom of the first post, and then tensioned, to transfer the load back down to the bottom end of the “lever.”

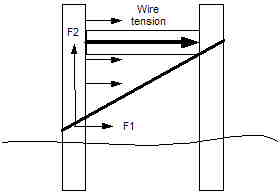

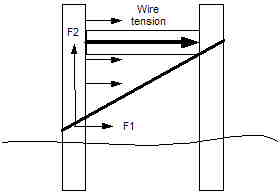

Above, you can see how the diagonal wire is going to pull on the bottom of the end post as a reaction to the cross-piece pushing on the second post. Physics 101 teaches you how to break down a diagonal force vector into is horizontal and vertical components (F1 and F2 in the diagram). You can do this mathematically using trigonometry, but here I’m just going to show it intuitively, the precise math isn’t as important as the general concept.

The goal is to create a “long” triangle as above, where the wire is pulling more in the horizontal direction (F1) than the vertical (F2). The vertical component of force (F2) is actually undesirable, because it’s going to encourage the post to pull up out of the soil, so we want that to be as small as we can manage. What we want is more F1 force, which will counteract the lever action happening at the top of the post, pulling it at the bottom to make it stay standing up straight.

The mistake many people make is creating too narrow of an H-brace, so that their diagonal wire has a very steep angle, instead of a very flat angle. This means there is more upward (F2) force than sideways (F1) force, so over time, the end post could possibly pop out of the ground from the vertical strain. The rule of thumb I’ve read is that you want angle no bigger than 45° from the ground, and preferably less. So make your H at least twice as wide as your fence is tall, though 2.5 times as wide is better.

The reason H-braces are the most popular method is that they are the easiest and cheapest to install. Merely:

1. drill holes for, and then pound in brace pins (foot-long rebar works well) to secure the cross-beam (you can notch the posts too, but it’s extra work, and doesn’t gain much),

2. use a heavy gauge wire for the diagonal, securing it with staples top and bottom (or you can hook it over a sticking-out brace pin at the top),

3. then tension the wire by twisting a “twitch” stick in the middle of it (or use a new-fangled, store-bought tensioner device) until its firm.

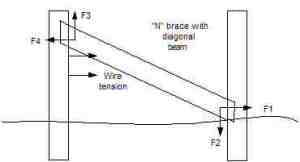

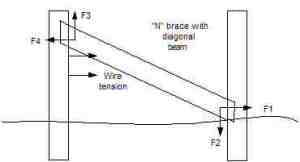

One alternative method to the H-brace is an “N” shaped brace. It involves making a diagonal out of another beam, that travels from the top of the end post down to the bottom of the second post, so that as the end post wants to “flip”, it’s pushing against a diagonal brace that resists this motion. The theory is good, but I think this method is less practical because first, you have to buy an expensive, long post to make that diagonal (a 10- or 12-footer for a 4′ high fence), rather than letting inexpensive wire be the long component. And, it’s more challenging to truly secure that diagonal to the end points, so that things won’t just “scoot” around, or cause nails to pop, when forces are applied. You need to do a fancier job of notching and securing, which is often inconvenient when you are way out in a pasture without power and your whole tool box. Wire is a lot easier to secure than an angled junction between to beams, especially for laymen.

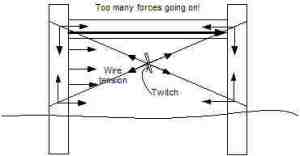

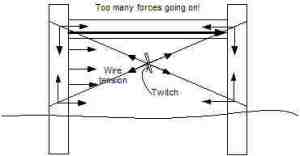

I’ve often seen examples of braces where someone put the diagonal wire in the wrong direction. This actually has zero affect long-term, because as the end post starts to lean, it’ll slacken the tension on the diagonal wire, such that it starts to do absolutely nothing. But when first built, the moment the diagonal wire is tensioned, it’s actually going to put more force on the top of the end post, causing it to want to lean more than ever! In this case, the only saving grace of the “H” is that the load is still shared between the two posts, which is better than nothing at all; but it’ll probably still fail over time.

Another mistake I’ve seen is people putting diagonal wires in both directions, and then tying them together by twisting the twitch stick in the middle of both. If you feel you must do two diagonals (which makes sense on an H-brace that’s mid-run on a long fence line, or if you have a gate pulling on an end post in the opposite direction of the fence tension), they must be independent of each other, so they can each counteract their own forces. If they are tied together, you are crippling the one that’s experiencing the most load, and transferring loads to places where you don’t want them. As you can see from the diagram below, there are 14 different force vectors to worry about, that are all influencing each other- way too complicated to get it right!

Here is how one of my H-braces turned out; I used 8’x6″x6″ treated timbers here for the posts, buried about 3′ deep; and a 8’x4″x4″ as the cross-beam, tilted slightly so water will run off it. The fence in this case is running off to the left. This brace is enduring quite a slope change; sometime maybe I’ll go back and cut off the second post a little shorter for aesthetic purposes to make it match! These seem to be holding strong, so far, under the tension of the newly-strung fence, knock on wood!

A handy tip I found in a book is to screw galvanized bolts about halfway into the posts where they will contact the concrete. This binds the concrete and post together, so that the post cannot slide or twist within its concrete shell. Here (left) is what I’ve been doing on the bottoms of my posts.

A handy tip I found in a book is to screw galvanized bolts about halfway into the posts where they will contact the concrete. This binds the concrete and post together, so that the post cannot slide or twist within its concrete shell. Here (left) is what I’ve been doing on the bottoms of my posts.